Maternal Mortality

Burkina Faso

The maternal mortality ratio in Burkina Faso decreased between 2000 and 2017, from 516 to 320 per 100,000 live births (WHO, 2019). Despite this significant change, several studies have documented that hemorrhage accounts for a significant proportion of maternal mortality. In 2020, hemorrhage accounted for 23.6% of maternal deaths in Burkina Faso health facilities (Ministry of Health, 2021).

Senegal

The maternal mortality ratio in Senegal declined from 434 to 392 deaths per 100,000 live births between 2005 and 2010/2011 (ANSD, 2012; N'Diaye & Ayad, 2006) and declined again to 273 in 2017 (ANSD and ICF, 2018). Despite these significant achievements, hemorrhage accounts for a significant proportion of maternal mortality. A 2015-2016 survey on the availability, use, and quality of emergency obstetric and neonatal care (EmONC) in 120 health facilities estimated that 26.4% of maternal deaths in Senegalese health facilities were related to postpartum hemorrhage (MSAS/DSRSE, UNFPA, and CEFOREP, 2017).

Legal Status of Abortion

Burkina Faso

Following an amendment in 1996, the penal code allows induced abortion under three circumstances: if carrying the pregnancy to term endangers the life and health of the pregnant woman; at the request of the pregnant woman when the pregnancy is the result of rape or incest; and fetal malformation (Storeng & Outtarra, 2014).

Despite these permissions, clandestine unsafe abortion remains a significant public health problem. One-third of pregnancies end in induced abortion (Bankole et al., 2013). More than half of induced abortions are unsafe (51%), and approximately 32% of women who have unsafe abortions experience complications (PMA 2021).

Senegal

The Senegalese penal code prohibits abortion under any circumstances. Although the medical code of ethics allows therapeutic abortion with the authorization of three physicians, in practice such abortions are rare (Suh, 2021b).

Despite these restrictions, women seek abortions, and complications of unsafe abortion are a significant public health problem. A 2014 national study estimated the incidence of abortion to be 17 per 1,000 women. Nearly a quarter of all pregnancies end in induced abortion. An estimated two-thirds of abortions are considered unsafe, whether performed by untrained practitioners or by the women themselves. Approximately 42% of women with complications from unsafe abortion do not receive care, with low-income women and women in rural areas least likely to receive care (Guttmacher Institute, 2015; Sedgh et al 2015).

Post-Abortion Care

Burkina Faso

To address the problem of unsafe abortion, the government introduced postabortion care in the late 1990s. Post-abortion care is now available throughout the health system, including in primary health care facilities. Since 2018, the government has included postabortion care in its free maternal health care program (Ouedragou and Juma, 2020). Despite these developments, it is estimated that only half of women who described potentially serious complications access a health facility for postabortion care (PMA 2021). In addition, women may experience poor quality care such as delays or inadequate pain medication when health workers suspect they have had an illegal abortion (Ouedragou and Juma, 2020).

Senegal

To address the problem of abortion-related mortality, the Ministry of Health introduced postabortion care in the 1990s. Between 2007 and 2015, 84% of primary-level facilities and 86% of referral-level facilities reported being able to perform uterine evacuation (Owolabi, Biddlecom, and Whitehead 2109). In 2016, approximately 73% of health facilities used manual vacuum aspiration to treat cases of incomplete abortion in the past three months (ANSD and ICF, 2016). Despite these developments, gaps in access and quality of postabortion care remain. Only 50 percent of primary-level facilities reported the ability to refer patients to the nearest hospital (Owolabi, Biddlecom, and Whitehead 2019). Women may experience poor quality care such as delays or threats to withhold care when health workers suspect that they have had an illegal abortion (Suh 2021b).

Testing Misoprostol’s Efficacy

Health authorities in Burkina Faso and Senegal have supported clinical trials to test the efficacy of misoprostol in managing post-abortion care and post-partum hemorrhage in public hospitals since the mid-2000s (Dao et al, 2007; Blum et al, 2010; Diadhiou et al., 2011; Schochet et al., 2012; Gaye et al., 2014; Diop et al., 2016).

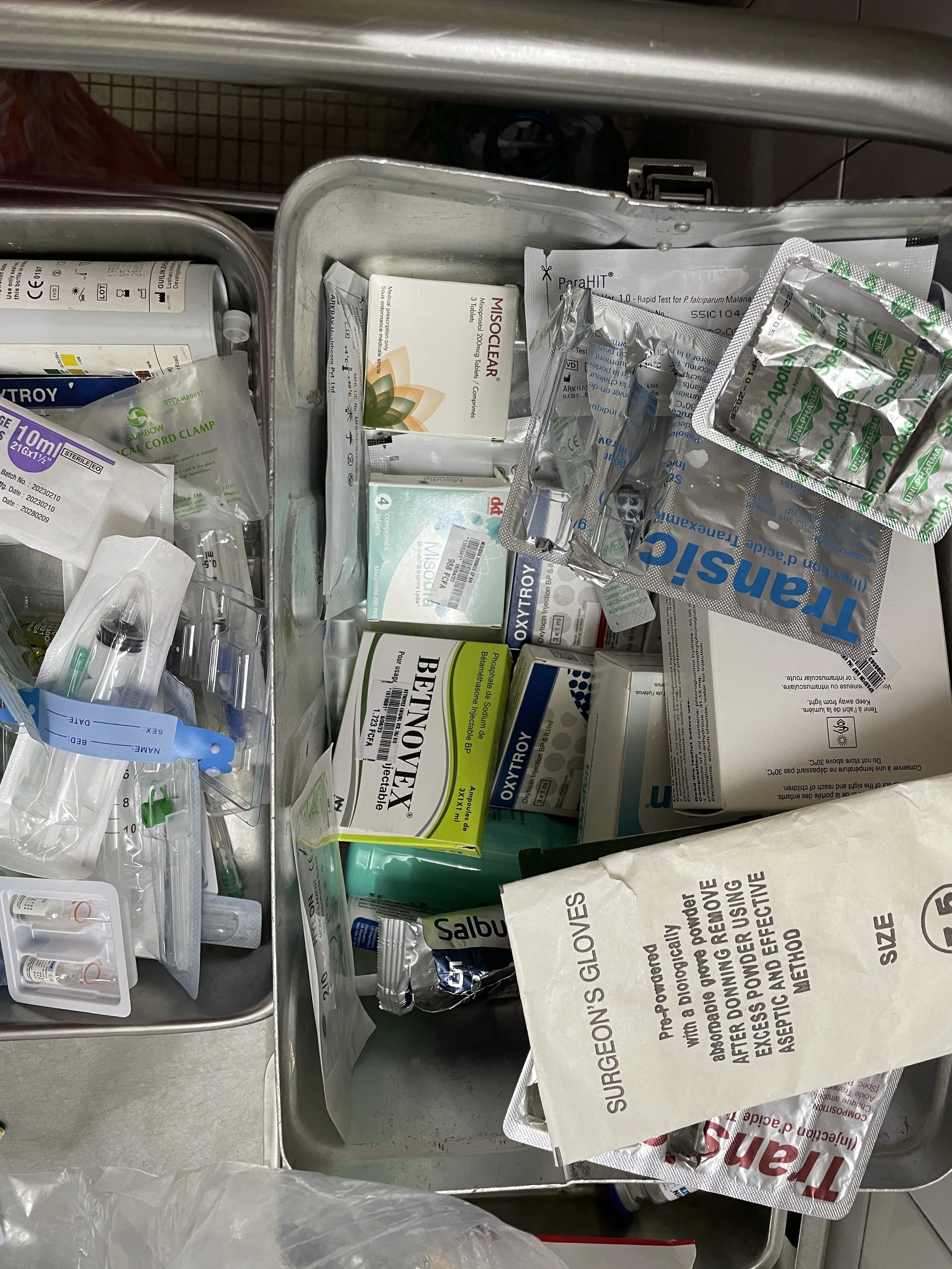

Registered Brands of Misoprostol

Burkina Faso

Misoprostol has been on the national essential drug list since 2014. Currently, there are three brands of misoprostol registered and available for purchase in Burkina Faso: Misobort, Misodia and Misoclear. There is also a "combi-pack" on the market that includes misoprostol and mifepristone (www.medab.org).

Senegal

In 2013, the Senegalese government listed misoprostol on its National List of Essential Medicines. Currently, there are three brands of misoprostol registered and available on the market: Misoclear, Misodia, and Misobort.

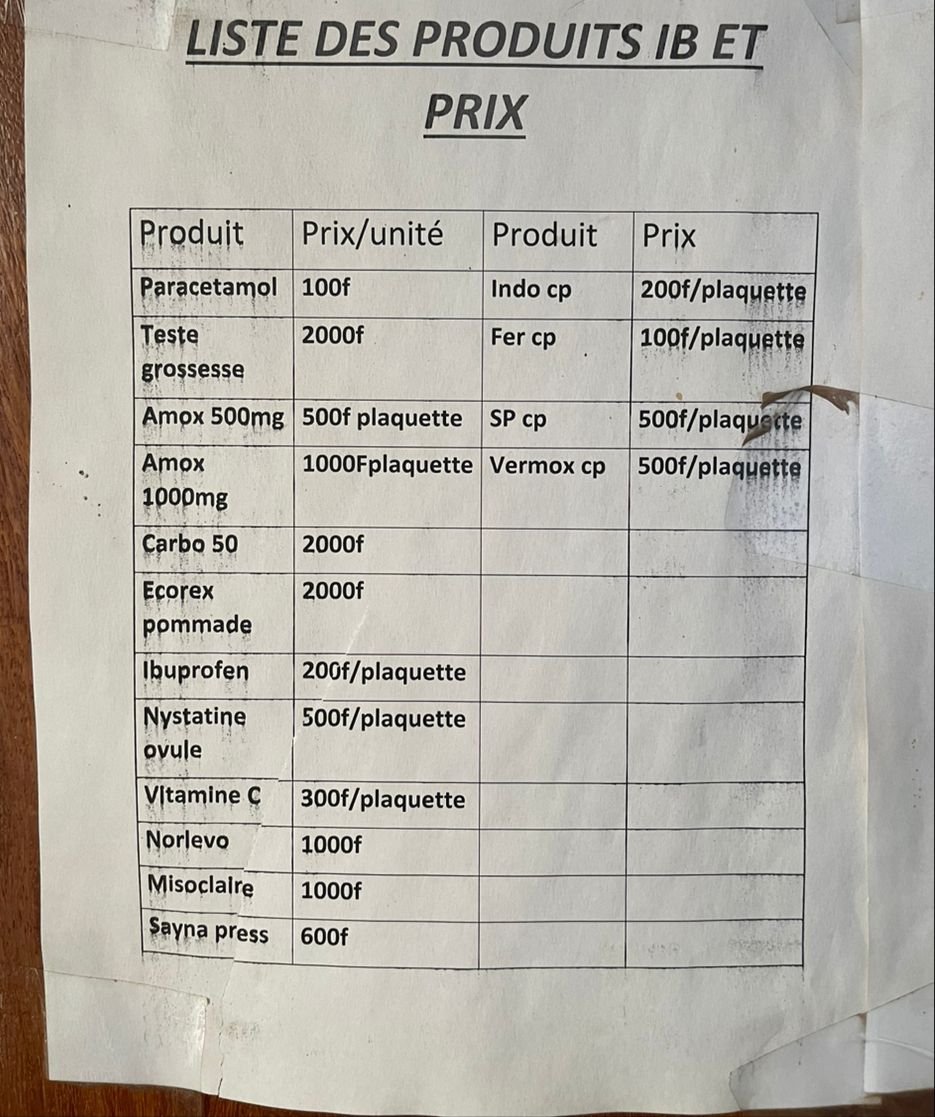

Misoprostol in Pharmacies and Health Facilities

Burkina Faso

A postabortion care study conducted between 2012 and 2014 at 56 health facilities with 6,316 patients found that misoprostol is used more frequently at lower levels of the health system. Misoprostol was most frequently used in health centers (45%) compared to regional hospitals (28.4%), medical centers with surgical units (22.5%), and teaching hospitals (14.8%) (Kiemtoré et al, 2016).

Senegal

A 2016 study estimated that only 3.4% of public health facilities (including hospitals, health centers, health posts, and clinics) had it available (nearly 90% of these facilities had oxytocin) (MSAS/DSRSE, UNFPA, and CEFOREP, 2017).